This piece was originally published March 14, 2009. The publication I worked for then let the post lapse into the void. But there were many copies.

Can you believe it’s really over? I can’t either. Before accepting that fact, let’s talk and think and write about the finale way too much. Here goes…

Part 1: The interview with Moore

MR: I think one thing that threw me about the finale was that it was hopeful.

RDM: [laughs] There were a fair number of people that were prepared for the most nihilistic [finale ever].

MR: “You’re going to kill them all, aren’t you!?”

RDM: I know.

MR: It’s the ultimate sucker punch of “Battlestar Galactica” — that it ends on a hopeful note.

RDM: Yeah, it’s true. It’s the final twist. The final twist is — that it’s all OK.

MR: Talk to me about that whole second Earth thing. That kind of gave me pause me when I saw it.

RDM: It was built into the show when we decided to get to Earth. This was always the plan – the plan was to get to Earth, have it be a cinder, and then go, “God, where now?” And take the audience on this other journey and make them forget about that and not think about it. Because the concept of the show was to search for a place called Earth.

So we wanted to give that to you before you expected it and make it a downer and [have you go,] “Oh shoot, now what?” And now you’re really adrift. [The intention was] to put the audience with the characters, where they were really adrift and not hoping that anything better was going to happen.

And at the very last, at the very end, to then have a moment of hope, to have something to hang on to, and to give them the thing that they had quested for for so long, and to give that to the audience too.

MR: And so it’s as if this Earth is an homage to the other Earth, the first one.

RDM: I thought there was something interesting about that. This isn’t the original Earth. We’re actually [living on] an homage, as you said, to the original Earth. They come here and try to learn a lesson from the original Earth and make this Earth a better story.

MR: So the question is, did they learn their lesson?

RDM: Exactly. And the show could not answer that. It didn’t feel right for the show, like [happens] with so many things, to give a definitive answer to that. Any more than the show said, “This is the answer to terrorism, this is the answer to Iraq, these are the answers to security and freedom.” It gets to a place where you have an opportunity and you have a hope, but you couldn’t definitively say, “It’s going to be OK.”

MR: I went back and watched the closing moments of “Crossroads, Part 2” again, and the final image is of a planet that looks a lot like Earth. How does that fit in to what we see in “Daybreak”? Can you walk me through that?

RDM: That was all specifically thought out. The planet that you see at the end of “Crossroads” is this planet that we stand on. It has the North American continent and the South American [continent], it’s very clear, we wanted it to be visually easy to identify for everybody.

Kara takes them to both Earths, as a matter of fact. She takes them to the original Earth, which, when we showed it in Revelations, we were careful to never quite be able to identify the land masses from orbit. We wanted you to accept it as Earth, and most people assumed it was this Earth, but we didn’t want to flat out mislead you, so we didn’t want to have it look like North America too.

MR: So Kara comes back in “Crossroads,” she says, “I’ve been to Earth”…

RDM: She had been to that Earth. The original Earth.

MR: The crispy Earth.

RDM: She guided the fleet to get there. She takes us to that. That’s part of her experience that she remembers. She remembers traveling there, seeing there, and comes back to the fleet saying, “I know how to get to that place.”

In the finale, she makes an intuitive leap connecting the music as coordinates, enters the into the jump computer and those coordinates take us to the second Earth, this place.

MR: It was a little bit of a fakeout, you have to admit.

RDM: Yeah, we did a head fake. But I don’t think it crosses the line, I don’t think it’s unduly misleading. I think you accept it as you go along. And clearly [we] wanted people to draw the connection that it was going to be this Earth, but we also didn’t put anything in the show that prevented us from doing the finale the way we wanted to.

MR: There has been some one or some thing orchestrating these events. And you purposely chose to leave that ambiguous.

RDM: It just felt like, you know, by its nature, the eternal, the divine, sort of defies concrete terminology. The more you attempt to state exactly what it is definitively, the less mysterious, the less supernatural, the less mysterious it becomes. And I thought, you can only go so far. You can kind of acknowledge a presence, you can acknowledge the hand of something else, and that was about as far as I thought that the show could comfortable show.

It was embedded in the mythology of the show since the miniseries, so that definitely had to be part of it, and it had to have a satisfying ending on that note, but I didn’t want to come right out and have a bearded guy in the heavens or something or sort of give voice to it. I just wanted to leave it mysterious. And as with so many things, the questions are more interesting than the answers are.

It’s almost inherently something we can know. It seems like it’s a continuing theme in mythology, that you can’t really know the divine. You can experience it, you can encounter it, things can be revealed to you, but you can never really understand the mysteries at the heart of it. And the more you try to put definitions on it, the less satisfying it becomes. Once you get to the place where you imagine God as a bearded guy in a cloud, it becomes less satisfying.

Baltar’s speech in CIC is pivotal — “There’s another presence here, we’ve all felt it, we’ve all seen its impact, we know it’s around us, we know it’s around us right now, and we have to have a leap of faith and trust that it’s there and believe that it exists, even if you can’t understand what it is and what its motivations are, if it has motivations.”

MR: Part of what I got from the flashbacks was this idea that these people are making choices of their own free will. They’re not just puppets on some divine strings.

RDM: Yeah. I think that’s true. That’s always one of the great contradictions of our existence, in a way. There are continuing themes in our lives that make us believe there is such a thing as fate, there is such a thing as destiny. And yet the belief that we have free will and we make our own decisions is equally powerful. Those two ideas are almost irreconcilable unless you believe that there is some sort of interplay between fate and free will that we can’t really delineate specifically.

It does feel like there’s a common thread of our existence, where we want to believe in both things strongly. We want to believe that we have a fate, a destiny, that we are meant to meet certain people, that we have soulmates, that certain people are born to achieve certain ends, that certain events are destined to happen, that are in the stars. Yet we also believe that we have free will and choice and that the decisions we make in our lives are meaningful.

MR: The Head characters, we’re to take them as representatives of that entity, the entity that we don’t necessarily define as good or evil?

RDM: I think one of the things the show has said from the beginning – you know, Leoben says, in the first season episode “Flesh and Bone,” he says, “What’s the first article of faith – ‘Is this all that we are? Is this all that I am? Isn’t there something more?’” And I still believe that that’s part and parcel of the human condition, is that we continually ask ourselves, “Is this all that there is? Is there something more?”

And the furthest the show could go is to say, “Yes, there’s something more, but you may not understand what it is. It’s something there, and it’s something you can touch into, and it may influence your life, but it defies religion and ideology and dogma. But there’s something.”

MR: Something actively participating…

RDM: Yeah, we are connected to it in some way.

MR: Were the flashbacks something you had in mind from the beginning, from when you started thinking about the finale?

RDM: They came in pretty late. It wasn’t until we were breaking the story, we were breaking the plot of how they were going to rescue Hera. We kind of had the general scheme of it — that Galactica would go fight the unfightable battle against the Cylons’ Colony, rescue Hera in some manner, the ship’s about to be destroyed and Kara would enter the “All Along the Watchtower” [theme as the jump coordinates] and that would take us to Earth. We knew that was the general direction.

We spent a day just in the room just chewing over plot: “How does Lee land? How does Kara get in? Which corridor are they going down?” It was frustrating and just kind of a pain in the [butt].

I went home, and I wasn’t very happy. Took a shower and in the shower and in the shower I has this epiphany — it was never about the plot. The joy of the show has always been in the characters. The next day on the whiteboard in the writers’ room, I wrote, “It’s the characters, stupid.” I said, “We’ll figure out the plot. There will be a plot, it will be good, we always manage to pull that stuff out, let’s trust in that for now, and let’s figure out what we want to do with these people.”

I said, “I have some images, I don’t know what I want to do with them. I have an image of a man in a house trying to chase a bird out with a broom. I don’t know who it is, but I like it and it’s somehow meaningful so let’s put it up on the board.”

I think it was David Weddle who talked about flashbacks or thinking about parts of their lives that we hadn’t seen. Part of the finale, in our heads, had always been about beginnings and endings. It was the end of the show, the end of the Galactica, the beginning of a new life on Earth.

We started talking about the miniseries and where the characters began, and the show bible, which has backstories for characters like Laura — I’d put the drunk driver and her sisters in the show bible but we’d never used it. We just started talking about a structure where we would have four or five stories told in flashbacks, and that that was really the A-story. The real story was about who these people were and how that informed their ending. That you would understand where they ended up by understanding where they began. All their flashback paths kind of take them too the show, and tell you who they were in the end.

Once we had that, the rest fell into place. The plot was pretty straightforward and it was exciting and we spent a lot of money and there was going to be a lot of bang and whoom and we just trusted that that was all going to work. And then it was just, who were these people in the flashbacks and what are the stories we want to tell?

MR: I think they gave where people ended up more weight. I actually got emotional when Baltar said, “You know, I know about farming.” I don’t think that would have had the same impact had we not seen him with his dad.

RDM: He was a person before the miniseries began. The miniseries posits him as Gauis Baltar, millionaire genius and playboy. But nobody’s really just like that. Everybody is complex and has families and crises and dramas and stuff they’re embarrassed about. This was a chance to open up Baltar a little bit more and, you know, he’s a person. And this was his journey too.

MR: I know that you don’t let yourself be guided by what you think the fan reaction might be, and you do what you feel is right for the show, but the ending of Kara – her just disappearing like that. That’ll certainly be a starting point for debate.

RDM: Oh yeah, it’ll be controversial. There will be people who will absolutely hate it and think that we failed in our mission. We debated it in the [writers] room, I thought about it a long time, and I had sort of the same answer. And the more I struggled to give definition to it, the less satisfying it became. There various avenues we went down, discussions, saying she’s specifically this or that. And every time it felt uninteresting and kind of pedestrian.

It felt like, if she’s truly connected to the Eternal, if she’s connected to this other power, this other thing in the universe, as long as you know she’s connected to it and she’s fulfilled her destiny, brought us to this place, brought us to two Earths, really, that’s enough. That should just be left to your imagination, left to your inquiry, left you to try to fill in the blanks we leave. That was my answer and I’m sure — I know – people will debate it.

MR: It worked for me, but I also wondered, has she been a Head character this whole time?

RDM: That’s a legitimate way to look at it too. We talked about that, that is a legitimate way to read it.

MR: But the Head characters can’t actually interact with the world, so it’s not quite that.

RDM: This is a different thing, so it doesn’t fit neatly into that category either.

MR: The more I think about it, the more I think the Starbuck debate might set the Internets on fire.

RDM: I have more than accepted the fact that there will be people who will never quite get over that.

MR: I had this experience the day after the finale, I was walking around in New York and became very emotional all of a sudden. I was thinking of that final scene between Adama and Kara and Lee and then the moment where Kara winks out of existence, and I thought of the phrase, “The father, the son and the Holy Ghost.” Having been raised Catholic, that just had so much resonance for me.

RDM: Yeah. I think it’s rooted firmly in traditions like that. We talked about that about that very idea, the Trinity, and Kara as somehow being representative or at least connected to that idea. We talked a lot about the resurrection of Christ and its mythology and how that plays into a woman who literally dies and comes back to life for a certain purpose and then leaves again and gives hope that there is something else. She sort of lives in all those kinds of thoughts.

MR: And thank you for making her a woman.

RDM: Yeah. [laughs] There you go.

MR: You’re really a pagan, that’s what it is.

RDM: Yeah, I kind of am.

MR: There’s part of you that likes ticking off the fans a little bit, right? [laughs] Do you ever anticipate it? Are there moments when you go, “I’m OK with this development, it works for me, and I think it’ll really tick people off!”

RDM: As long as I’m pretty secure in what it is and the reasons why we’re doing it, as long as we’re not doing it just to tick them off. This is very much in that ballpark. We had lots of discussions about it, we explored lots of different avenues, and they were just all unsatisfying. If she just sprouted wings and flew up to the clouds, it would not be a satisfying ending. It just wouldn’t. We never heard and I have yet to hear a concrete definition of Kara Thrace that becomes more satisfying than what we have.

What we have a has a sort of poetry and mystery to it and preserves the mystery and sort of lets people debate and think and wonder what she meant and where she came from and what that was all about. And it’s also clear that she was about getting them to their salvation. She was the harbinger of death, and brought them to that, and she was the harbinger of life and brought them to that as well.

MR: It’s interesting that your show provides these kinds of philosophical debate, but then there’s that first hour, where there’s all this awesome action and amazing scenes of robots fighting.

RDM: That’s in our DNA, that’s the DNA of “Battlestar Galactica.”

MR: That first hour, it’s also funny.

RDM: Yeah, it’s got humor, it’s a roller coaster.

MR: Was it your idea to have the old-school Centurions and new Centurions decking each other?

RDM: No, that’s something [FX supervisor] Gary Hutzel and his guys came up with. And I laughed and said, “Sure.”

MR: So just how over budget did you go? I was looking at that first hour going, “Wow, they really broke the bank.”

RDM: It was written as a two-hour [episode], it was budgeted as a two-hour [episode]. The script came in, the production staff looked at it, worried about it. It was a reality check. There was no way could do it on a two-hour budget and a two-hour time constraint. And the studio stepped up to the plate.

What I discovered, and I always knew this through the process of the show, but this really made it clear — the people at the studio and the network were as big of fans as we were. And they moved heaven and Earth to essentially – they budgeted an extra hour. Once they added an extra hour, suddenly we had a whole extra hour’s budget to work with, with the exact same script.

MR: I understand the network’s needs, but I wish we’d seen it all at once. That first hour really works best as part of a whole.

RDM: Well, that’s the thing. I argued very long and hard against doing that. It was not written that way. In fact, when I wrote the script, it was not even written as acts [i.e. Act 1, Act 2, Act 3]. I wrote the script as a two-hour movie and it was meant to be seen that way. But it was one of those things where it was like, “Well, they’re giving you the extra money…”

MR: “So just shut up.”

RDM: Just shut up at a certain point and move on. They wanted, for their own scheduling purposes, they felt that people were just not going to commit to tuning in at 8 p.m. for a show they were used to seeing later, nobody watches a three-hour movie, everybody watches a two-hour movie, blah blah blah. Episode 21 [“Daybreak, Part 1”], it’s not an episode. It’s a completely unsatisfying experience. I know that, because it was never intended to be [on its own].

MR: It’s just the first act of a play.

RDM: It’s the first act of a play. It doesn’t make any sense, it doesn’t have a coherent arc to it. It’s just a chunk that’s been broken off. I did manage to get them to agree to show all three hours this Friday. My hope is that some people will watch all three or at least they’ll watch them all together. It’ll live forever on DVD and they’ll watch it that way, and that’s the way it was always intended to be seen.

MR: You know very well that you can’t please everyone. To me, this half of the season has been very much about taking the characters to the end of their journeys. I think that pleases one group of fans. As you know, there are other fans who are like, “Answer the damn questions, Moore! What is the Opera House? What is Starbuck?” My feeling was, if a reasonable amount of those questions are answered and a reasonable amount of character finality takes place, then I’m OK with it. In that sense, that’s what I was looking for with the finale.

RDM: I felt as we approached the second half of the season, and even the midpoint, “Let’s choose plot threads that we’re going to wrap up before the finale.” I didn’t want the final Cylon to be hanging, because then the whole finale would be about the final Cylon. I didn’t want it to be about when they’re going to find Earth. Let’s get that out of the way at least so the audience stops thinking about it. Let’s explain the backstory of the Final Five and where they came from and who they are and where Cavil and the other skinjobs came from. Let’s answer some questions along the way and then let’s decide. Let’s be smart about it and say, “What are the things we’re going to hold ’til the very end?”

MR: And the Opera House visions — were those, again, that entity speaking to these characters?

RDM: It was moving them towards a certain moment that would prove to be crucial, they had to take certain actions in certain ways, in order to enable the final drama to play through. Head Six’s interaction with Baltar was necessary because she had to get him to a place where he believed in God, or believed in the possibility of God as a concept or the supernatural in order to make the speech in CIC with Brother Cavil at that key moment.

MR: And actually believe it for once.

RDM: And actually believe it. And do it in a heartfelt way and make an earnest argument, to get Cavil to not kill Hera or not take her – to make everything else possible.

MR: One of my biggest outstanding questions was whether you would pay off the Cally story line. She got very little justice in life and I wanted her to get justice in death. I actually said this in a comment on my site, “They’re not going to answer the Cally thing, are they?” I am the worst predictor of anything, ever.

RDM: See, I deliberately buried that too. I said, let’s not even talk about Tory and Cally again. Let’s bury that card deep in the deck and then at this moment, when you’re not even remotely thinking about it, let’s play that card. And then likewise, when you’re not even thinking about Earth, let’s play that card.

MR: Tyrol killing Tory — that seemed like the kind of thing that would start the cycle of violence and hate again. It can be read so many ways, though. You could say, that was justice for Cally.

RDM: There’s that. I was also interested in the idea that, out of the human emotions of vengeance and anger and murder came their final salvation at the same time. That there’s this weird, contradictory currents through our lives — amazing great things come out of horrible deeds, and vice versa. I wanted to play a last note on that and to make it, sort of, “What do we think about that? How do we feel about that moment?” It was all coming to a moment of resolution, and you kind of want to condemn him for it, and then you look at what happened after that, and you kind of want to celebrate him for it. You’re caught between these two impulses and I like that.

MR: That’s getting me thinking about that scene between Athena and Boomer — I can see how it may be wrong to kill Boomer, but at the same time, I can see Athena wanting to protect her child at all costs.

RDM: And it was meant to be that Boomer had pretty much made her choice. She knew and accepted and kind of wanted to die.

MR: We got so much mythology about Hera and how important she was. In the end, was she important just because she was a living, sentient being and not just a lab rat or an oracle?

RDM: There’s all that, but she’s also literally the embodiment of the human and the Cylon race and that literally becomes who we are. In the end, all of use are the children of Hera, which means we’re the children of all these people we’ve witnessed throughout the show. Their humanity survives through us, so do the Cylons.

MR: So that dream of the two races living together — she was the embodiment of that.

RDM: Yeah, she was the embodiment of that. As are we.

MR: James Poniewozik emailed me a question, here it is: “It seems to me like we pretty much are repeating the ‘cycle.’ So wouldn’t we have been better off if the fleet had just offed themselves? Or at least, just given us the technology and kept their philosophy/gods/etc, instead of the other way around?”

RDM: Well, I guess that depends on what happens from here on out. It seemed like the cycle has come to another key point. The cycle can still be broken, and the question is, like they say at the end, will it be broken? It leaves it unanswered and I don’t think there is an answer.

MR: It’s up to us, I guess.

RDM: That’s where we wanted the show ultimately to get to — it’s up to us.

MR: What was the decision like to put yourself in that final scene? Was that a long debate that you had or what?

RDM: You know what? I just thought it was a lark, I thought, “I’m going to be that guy at the newsstand reading a magazine.” It was like this little weird cameo. Every time I watch it now, I start flinching, and feeling like I shouldn’t have done that, because it really distracts me when I watch it. And I feel like it’s going to distract people. It’s like, [expletive], I didn’t mean it to be so prominent. I just thought it would be a fun little deal, and it’s sort of a bigger presence on camera than I thought.

MR: I guess maybe from an aesthetic standpoint or a journey-ending standpoint, part of me thought it would be really beautiful to end the entire series on that shot of Adama on the hillside with Laura Roslin’s grave. Was that ever a thought or did you have that image of Caprica Six in Times Square and that was what you wanted?

RDM: We had that image a couple years ago. I always wanted to get to there. That image — Times Square in the modern day — only works in terms of servicing the Hera story. It really is about paying off Hera’s story. That last scene is really all about her, why she was important, who are we, “Oh my God, we’re connected to her and the Cylons,” and the cycle of time and will it repeat? It seemed like that sort of grander arc in the show demanded that it also sort of be resolved and it be resolved on that note.

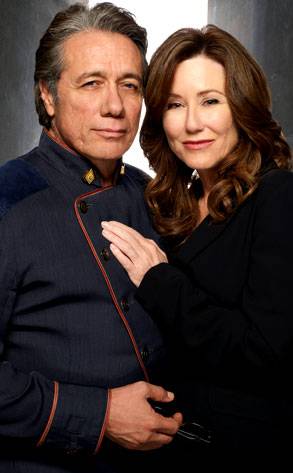

Part 2: Remarks by Edward James Olmos, Mary McDonnell, Ron Moore and David Eick after the finale screening on March 16.

I have not transcribed every single word of this panel. Because at this stage, my fingers are in danger of falling off after all the transcription I’ve done lately.

Was Kara just an angel, and were we all chasing down a rabbit hole or something when we assumed that her father was Daniel, this missing eighth Cylon?

RDM: Daniel was definitely a rabbit hole. It was an unintentional rabbit hole, to be honest. I was kind of surprised when I began picking up on speculation online among people that Daniel – [who was,] for those of you who don’t know, a deep part of the Cylon backstory that had to do with one of the Cylon skinjobs that was created by the Final Five, who was sort of aborted by Brother Cavil in the deep, deep backstory of the show. It was always intended just to be sort of an interesting bit of backstory about Cavil, his jealousy, a sort of Cain and Abel allegory. Then people started really grabbing on to it and seizing on it as some major part of the mythology. In a couple of interviews and in the last podcast, I’ve gone out of my way to say, “Don’t spend too much time and energy on this particular theory, because it was never intended to be that major a piece of the mythology.” It was never intended to take that kind of load-bearing weight.

DE: It’s like Boxey in that way.

RDM: Kara is what you want her to be. I think Kara – it’s easy to put a label on her of angel or messenger of God or something like that. Kara Thrace died and resurrected and [inaudible] and took people to their final end, and that was sort of her role, her destiny in the show. That’s sort of the long and the short of it. We debated back and forth in the writers room for a while about giving more definition, giving her more clarity and saying “This is definitively what she is.” And we started to say, the more you try to sort of outline and give voice to and put a name on it, the less interesting it became, and we just decided this was the most interesting way to go out, with her just disappearing and [you’re] wondering just exactly what she was.

Are we to assume that there are a lot of pissed-off Cavils out there still, or …there’s no definitive answer, or they were destroyed?

RDM: Well, the final final [cut] came out a little less clear on that level than I certainly intended. It’s one of those things we didn’t quite see through all the way to the end. It was scripted and the idea was, that when Racetrack bumps [the button on the controls], hits the nukes, the nukes come in, smack into the Colony, takes the Colony out of the stream that was swirling around the singularity and it fell in and was destroyed and torn apart. I think as we went through the show and kept pulling out [moments for] time and we kept cutting frames and doing this and that, one of the things that became less apparent was that the Colony was doomed.

At what point, Ron, did you decide to make it Earth in the past that were going to wind up at, and what was your reasoning for that?

RDM: We decided that quite a while ago, a couple of years ago. I don’t think we ever really had a version of the show where we talked about it being in the future of being in the present. Those didn’t seem as interesting. We sort of, in the early going, [began to] started talking about the fact that we would see a lot of contemporary things in the show, from language to wardrobe to all sorts of production design details. And that only made sense to us in terms of, actually a lot of the things that we see in the show and we feel are taken from our contemporary world are actually theirs to begin with and somehow spread down through the eons and came down to us through the collective unconscious or [inaudible].

DE: There was a time when we were talking about literally, you know, they land and it’s pterydactls and Tyrannosaurus rex. But it was really the idea that they were part of the sort of genus of humankind and this seemed like the right and more affordable way to do that than “Jurassic Park.” [laughter]

RDM: We had the idea of Six walking through Times Square – we came up with a long time ago.

Do you have any clues as to who attacked the original Earth… and why did Cavil shoot himself?

RDM: The backstory of the original Earth was supposed to be that the 13th Tribe of Cylons came to that world, started over and essentially destroyed themselves. There was some internecine warfare that occurred among the Cylons themselves, which was another repetition of the cycles “all this has happened before and will happen again.” …

Cavil killing himself came from Dean Stockwell. [in the script, Tigh was supposed to fling over the edge of a higher level in the CIC.] Dean called me himself and said, “You know, I just really think that in that moment, Cavil would realize the jig is up and it’s all hopeless and just put a gun in his mouth and shoot himself.

This is for the actors, what was the last scene you filmed and how hard was it to complete that?

MM: My last scene was my last scene, it was Laura Roslin’s last moment in the Raptor. And that was at about 4:45 a.m., on a very small set. I think I was one of the first people to wrap. And she died. My son and I went to the airport and flew to L.A. [laughs] It happened quickly, it wasn’t set to happen then, it was set to happen a week later. And the schedule was changed.

EJO: My last day was the [last shot of Adama] on the mountainside. It was the last moment that I’m on camera. It was quite an experience all the way around, that moment in time. It was real easy. I think everybody had a real easy time with the emotions that we had at the very end.

[To sum up part of the question, it was about the Watchtower theme/”All Along the Watchtower”] Are you trying to get at some notion that this is some kind of universal consciousness that goes back as far as the human and Cylon races have been in existence. Or is there some history to the song in this narrative that I’m missing?

RDM: Yes [laughter]. The notion is sort of what you posited. The music, lyrics, the composition is divine, it’s eternal, it’s something that lives in the collective unconsciousness of everyone on the show. … It’s sort of a connection of the divine and the mortal. Music is something people literally catch out of the air, they can’t really tell you and define exactly how they compose it. Here is a song that transcends many eons and many different people and cultures, literally across the stars, and ultimately was reinvented by one Mr. Bob Dylan.

DE: It was a simple way, I thought to communicate clearly that this is not the future, that this is a story [that related] to ours. [There was a plan to introduce the song in Season 1 but they ended up feeling it was too soon.] We were thinking about it that far back, that music would be a great way to say to the audience, “No, no, this all follows that cyclical theme of this has all happened before and it will happen again.” This culture is the one that gave birth to ours… [All the slang and cultural stuff,] we get that from them, not the other way around.

[Setting an end date] — did that right the ship in some ways or change the process for you?

RDM: Well, I know in terms of the writers room, it certainly focused us. We kind of made the decision that the fourth season would be the last season at the end of the third season. [It made them more focused and specific about ending the show.] Part of the motivation to make it the final season was that we didn’t want to get to the place that we felt like the ship was keeling over and had a problem. We also instinctively felt the show has reached the third act by the time it got to the end of that third season. [He added that there was a more intense energy level on the set in the final season.]

MM: As you are able to do when you’re doing a play, you can then kind of kick into gear and plot your finish. And what that ends up doing is simplifying things for you because you know where you’re headed. And you can let go. … I think a lot of us felt a kind of simplification and a humility that came over us. It gives you a lot of energy. You just know where you’re going and proud to be a part of it and you let go.

EJO: We had a meeting at the very beginning of the show … in my trailer … 13 of us.

MM: He had the biggest trailer. It really was great, we really miss our trailers.

EJO: We sat down and discussed what we were doing and what the possibilities were. We talked about making sure that we understood that if by chance … [the show] was to move forward as a series … that we had to understand that. I don’t think anyone had done a complete series. Had you?

MM: No, I never made it past 13 [episodes].

EJO: We finished “Miami Vice,” we did five years, but we never really had a finish with it. There was never some plan. … I just know if we did this, we would go through this story and the story would have a beginning, a middle and an end. And that we had to pace ourselves. So [starting] the fourth season, we had a meeting and we were told then that this was going to be the final season. So everyone got very, very depressed. I don’t think anyone wanted to stop the show. Ron made it very clear from the conception that there was a beginning, a middle and an end. And we had hit the end.

So in our meeting, we talked about the very first time we’d gotten together. And [we said] it’s a marathon. In a marathon you have to … start out strong. The next 25 miles has to be consistent. … Then the last mile has to be the strongest mile. We all knew that going into the final [season].

That very last scene, the Head characters, are they angels or are they demons?

RDM: Well, I think they’re both. WE never tried to name exactly what the Head characters [are]. …We never really looked at them as angels or demons because they seemed to periodically say evil things and good things and they tended to save peple and tended to damn people and there was a sense that they were in the service of something else… that was guiding, helping, sometimes obstructing, sometimes tempting the mortal people on the show. The idea at the very end was, whatever they are in service of continues and is eternal and is always around and they too are still here with us, with all of us who are the children of Hera. …

Part 3: A few words from Mary McDonnell

MR: You’ve attended a lot of events during your career – is this one special to you?

MM: Totally. Because it’s brand new. It’s something I’ve never experienced before. Very few of us have experienced this idea, that policy and ideas that come from the collective can be supported by the entertainment industry in a way that has no political agenda. It’s really about connecting to human rights, that’s really what the whole thing is about.

MR: I think “Battlestar” would never have worked had the writers had this list of, “Here are important topics we’re going to bring up.”

MM: It wouldn’t work. Ron knows that almost better than anyone. He creates from a place that doesn’t seem to be conscious of what people need. He has an instinct for it. It’s in his subconscious. But because he isn’t trying to teach anyone anything, he incorporates the human experience, which includes a great deal of humor and a great deal of complexity. He’s kind of a master at this at understanding this. I don’t think he really knew [it would eventually get this kind of reception].

MR: Yeah, six years ago, who knew your show would end up here?

MM: This and the AFI Awards and the Peabody Award – these feel like the path of this show. The sort of destiny of the show. If eventually the Emmys become a part of that, that’s wonderful, but that doesn’t seem to be the end of the line. This is the point. The point of this show is that something like this can happen.

MR: You said something on the panel, about how the goal of the artist is to connect with the world.

MM: Completely there’s no other reason to do it. The experience of doing it means nothing unless you feel like you’ve connected to the people at large. And in this experience [with the fans of the show], the people are so smart, so verbal, and they give so much back that you feel like you’ve just been given a warm bath.

MR: The young people that were here, they had some good questions. It seems like they wonder about technology more than we do.

MM: They know that they are the leaders of all the technology [developments]. They have questions, they don’t really know how to bring their compassion along. They’re trying to figure out — how do we tie the human element of our heart and compassion into this quickly evolving mechanism we’re using. They’re afraid they’re going to lose something and to a certain extent, they will, if technology and the heart don’t connect. And I think Ron is trying to talk about that.

MR: Because the whole show is about connecting.

MM: Right. Totally.

Part 4: My thoughts on the finale

Wow.

We didn’t just get one finale, we got two.

There was the first hour, and then there was the final hour. I had different reactions to each hour. But overall, I loved it.

It was pretty frakkin’ wonderful.

There were a few things that gave me pause the first time around. You can see what those things were in the interview above — I asked Ron Moore a lot of questions about things I wanted to understand more. When I watched the finale again on Friday, having had a few days to digest my first viewing of the finale, it all came together for me, even more than it did the first time.

I felt a wonderful sense of closure. Bear McCreary’s music once again moved me on a molecular level. As did the performances and the bittersweet sadness as we all said goodbye — the characters to each other, the actors to these roles, the audience to this complex and confounding and compelling world.

Finales are notoriously difficult to do — so few shows have done them well. But “Battlestar” showed me where everyone ended up and gave me things to think about along the way.

Plus, Centurions fighting! GODS!

Words can’t begin to convey how much I loved the first hour of “Daylight” (it’s actually the second hour — as Moore said above, all of “Daylight” works much better when you see all three hours of the finale together).

I flat-out, 200 percent, absolutely and with fist-pumping glee looooooved what transpired from the moment Adama drew the red line down the center of the hanger deck until the moment the Galactica jumped away from the Colony.

It’s not just one of the finest hours “Battlestar” has ever done, it’s one of the finest hours of television I’ve ever seen. I felt like a 10 year old kid watching “Star Wars.” Thank you, Gary Hutzel and crew: Those battle scenes made me positively giddy.

Come on, old-school Centurions and new-school Centurions in hand-to-hand combat? The finale could have featured Boxey as a deus ex machina and I would have forgiven even that. That’s how good the battle and combat sequences were.

Still, it wasn’t just the extraordinarily exciting space battles that thrilled me, though once again Hutzel and his team outdid themselves. And it wasn’t just the sheer excitement of watching nearly every single character engaging in combat, even frakkin’ Baltar. (So his one moment of combat glory involved him shooting a Centurion that was already down. Whatever. He still strapped on a gun and made the attempt. As my friend Andrew said, by not leaving the Galactica, he “pulled a Han Solo.” Respect.)

Each of those elements was great on its own. But it all added up to something even more wonderful than the sum of the constituent parts.

The visuals, the mood, the atmosphere, the terse dialogue – it all came together to masterfully convey a sense of impending doom and a feeling of finality. There was the installation of Anders in CIC, his wires looming over the crew like the web of a great spider. There was sight of Centurions on the flight deck, something we thought we’d never see. There were glimpses of the crew, planning their assault, which promised to be bloody and difficult. And there was that scene of Cottle and Laura, which was made of awesome.

And there had to be one last “into the breach” exhortation from Adama: “She will not fail us if we don’t fail her.”

By gods, the old girl didn’t fail them. Even after they rammed her into the Colony. Wow.

All that, and they brought the funny, too.

I certainly wasn’t expecting the finale of this show to make me laugh, but how could you not laugh at the idea of President Lampkin? (I want it known that if there was a spinoff involving President Lampkin and Admiral Hoshi, I would totally watch that show.). How about Baltar when we first glimpsed him in his battle gear? Faintly but disinctly hilarious.

Then there was Tigh’s suggestion to Adama regarding the Cylons: “It’s still not too late to flush them all out the airlock.”

Aside from the jokes, the raid on the Colony contained some key character moments as well. There was Cavil, once again proving, through his snarky asides to Doral and Simon, that he’s possibly the universe’s worst boss (seriously, why did those other Cylon models stick with him for so long? Really, working for Michael Scott or even Dwight Schrute seems preferable).

There was Boomer and Athena’s encounter. (And even that had its share of humor. When it appeared that Athena might spill the beans about what their plan was, Starbuck interjected, “Can you not tell her the plan?”)

Boomer gave Hera back to Athena, but it was too little, too late, in Athena’s eyes. She killed Boomer. I can see how that might scar little Hera for life – to see one copy of Mommy kill another – but I can see how, in Athena’s eyes, there was only one way to be rid of the troublesome Boomer forever. If that’s what it took to protect her child, she would do it.

We saw a flashback of Boomer and the Old Man, back when she was still a new pilot. He allowed her to stay on his ship, despite the fact that she couldn’t stick her landings. She promised to pay Adama back one day for his continued faith in her.

And that’s what all those flashbacks told us; when these characters made the key decisions that put their lives on this course. Boomer stayed with the Galactica instead of bailing out, and that brought her to this moment. Adama stayed in the service, rather than bail out for a cushy job in the private sector. Rather than waste her time on affairs with (admittedly hot) younger men, Roslin chose to join Adar’s campaign, which eventually brought her to the Galactica.

Something about these characters’ basic natures asserted themselves in those moments, and thus, in a way, they orchestrated their own fates. There may have been some divine force guiding events, but these people chose these paths.

I suppose I had a little trouble with the Lee-Starbuck flashback. You could see that Lee fell in love with her almost from the moment he saw her. But she certainly seemed to be in love with Zak. It’s no secret that Starbuck could be a self-destructive party girl, but all it took for her to put the moves on her boyfriend’s brother was a few drinks and one philosophical late-night conversation? I don’t know. I thought Starbuck was capable of more loyalty than that. Still, she and Lee didn’t actually do anything major, and there’s every chance she let Zak pass his basic flight course not just because she wanted to stay with him but because she felt guilty about her attraction to his brother.

That’s our Starbuck — complicated and conflicted ’til the end.

In any case, the flashbacks and the rest of the scenes, throughout these final hours, reminded me of a symphony. There were movements, themes, moods, all orchestrated to bring us to a final resting place. We got closure. We had moments of great emotion. And I’m going to say it again — all of the music was gorgeous. The Celtic melodies, the Opera House music, the Watchtower theme.

As Kara keyed in the coordinates of that final jump, McCreary’s music raised the hair on the back of my neck. There’s one word in my handwritten notes for this sequence: “Amazing.”

Now, my response to the first hour was just sheer, uncomplicated pleasure. The second hour gave me a few pauses the first time around, as I noted above. But I must admit, in all honesty, the second time around, those things didn’t really give me much pause. I’m sure there are things we could nitpick all day, but I’m so not in a mood to nitpick. Not when I’ve just seen this show, in a very major way, stick the landing.

I have a feeling some will be angry about Starbuck just disappearing. I have a feeling some people will hate that. Not only did we not find out definitively who or what re-made her and sent her back to the fleet (and how that was done), when all was said and done, she just winked out of existence.

I was perfectly at peace with the disappearance of Starbuck. I didn’t know why until the day after the finale, when I was walking down Madison Avenue in New York City and it hit me like a thunderbolt.

The Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost.

I’m not going to make some tortured analogy about Lee, Adama and Starbuck representing the Trinity, because, though it is intriguing, it doesn’t completely hold up. But still, having been raised Catholic, there was something powerfully right about that idea. Lapsed as I am, it made sense to me on a subconscious, instinctual level. Those three have always been the center of the show, and it just struck me why those central relationships always resonated so strongly, for me anyway.

Having been raised from birth with ideas about the workings of the Holy Ghost (that was even the name of our parish), something about Starbuck just fit that idea, the idea of a divine influencer. A holy spirit.

Another thought about Starbuck: I recently came across this passage in the “Dhammapada,” a foundational Buddhist text. Here are verses 346-348 (from the 2005 Shambhala Publications translation by Gil Fronsdal):

“Having cut even this, they go forth,

Free from longing, abandoning sensual pleasures.

Those attached to passion

Are caught in a river [of their own making]

Like a spider caught in its own web.

But having cut even this, the wise set forth,

Free from longing, abandoning all suffering.

“Let go of the past, let go of the future,

Let go of the present.

Gone beyond becoming,

With the mind released in every way,

You do not again undergo birth and old age.”

How gorgeous is that phrase: “Gone beyond becoming.”

To me, that’s where Starbuck is. And after everything she’s been through, she deserves to be at rest, wherever, whatever she is. She deserves to break her own personal cycle of pain and longing. Godspeed, Starbuck.

As for the final moments, there were so many beautiful images in the last hour of finale — the fleet heading toward the sun, Starbuck saying goodbye to Anders, Adama taking out a Viper one last time.

Adama saying goodbye to Lee and Starbuck was gracefully handled. I loved the callback to their first conversation in the miniseries: “What do you hear, Starbuck?” “Nothing but the rain.” “Grab your gun and bring in the cat.”

Baltar and Caprica Six finding their way toward real love throughout the finale was beautiful to see, and for some reason, right at the end, when his voice broke as he said, “You know, I know about farming,” it made me nearly cry. This was Baltar finally acknowledging his past, finally becoming a real person. Who would have thought the callous skirt-chaser glimpsed in the flashbacks would ever be capable of such real humanity?

And then there were the Roslin-Adama moments, and they were the most moving of all. If you can think about Adama putting his ring on her finger without getting choked up…. Well, I can’t.

That final image of Adama sitting on that hill would have been a lovely way to end the series. I actually did think that was the ending, until suddenly we were confronted with a very different image — a modern metropolis 150,000 years later.

My biggest objection to the finale — and it’s not an “oh they ruined it” one — is this: I really, really disliked the footage of the robots in that final scene. For a show that often came at things subtly, everything about that robot footage and other aspects of the scene felt much too obvious.

Actually, the entire scene was quite different from what came before. It was quite a tonal switch. It was jarring to go from such lyrical moments to such exposition-y stuff. (And if you know what he looks like — and perhaps the majority of “Battlestar” fans don’t — seeing Moore in the scene was odd too. It took me out of the moment).

Still. Having enjoyed so many other things about the finale, I’m just going to let that one go.

So. In closing. There can be no summing up.

I don’t know how to say goodbye to this show (and I guess with “The Plan” to look forward to, I can just pretend it’s “au revoir”).

My words are failing, so I’m going to steal someone else’s. In the “Battlestar Galactica in the Media” thread on Television Without Pity, a debate began about “BSG” vs “The Wire” (the discussion continued on the “BSG Comparisons” board). The discussion was prompted by a piece in the Guardian calling “BSG” better than “The Wire.”

By law, TV critics are required to call “The Wire” important, great, amazing, ambitious and so forth. It is all those things, without a doubt. If we’re talking just about sheer consistency, “The Wire” (and “The Shield,” for that matter) beat almost all comers, including “BSG.” (Know that I understand that there is no “best” TV series and there can be no winner of that debate.)

But this statement from Effra sums up my feelings perfectly.

“…If I had to choose to have only seen one of them, I would choose ‘Battlestar’ every single time. ‘The Wire’ is an extraordinary testament to a particular time and place and the kind of lives that are lived in Baltimore and cities like it. ‘Battlestar’ is an even more extraordinary meditation on the human condition that to me stands up there with some of the great mythological stories about that. It also gives an emotional way for us to think about it for own lives in the way ‘The Wire’ can’t, unless one is living a life like those in Baltimore.

“I learned a lot from watching ‘The Wire’ and I thought about things I hadn’t thought about before. But it didn’t get into my soul. ‘Battlestar’ has and it will stay there.”

That’s it. “Battlestar” got into my soul.

No other show has reached into the core of my being and made me physically feel so much: Fear, nausea, anxiety, excitement, tension, exhilaration, joy. Sometimes I cried, other times — as during much of the first hour of the finale — it made me want to stand up and cheer.

Throughout its four seasons, through the wobbles and the detours and the shocks and the amazing moments and the revelatory beauty, this show mixed action, philosophy, human emotion and compassion in a way I’ve never encountered before.

And I fear that all this… won’t happen again.

I’ll miss the way this show moved me. I’ll miss these people. I’ll miss the great action and the space battles and the mordant humor and even the misfires, because as this show often pointed out, mistakes are what make us human.

I feel incredibly sentimental right now, as I think about the fact that “Battlestar” began around the time that I began writing about television. It forced me to be better at my job.

It forced me to think harder, to write better, to be more rigorous. And this job has granted me many pleasures, but one of the biggest was turning friends, family and readers into raving fans of Adama, Roslin, Starbuck and the rest.

I’ll miss this flickering electronic campfire we all sat around every Friday, talking about our reactions to the story we’d just been told.

Thanks to everyone who made the show.

Thanks to all the readers who joined in these discussions.

Three cheers for the grand old lady.

So say we all!